By: Shoaib A. Rahim-The New Silk Road initiative of the United States came to life in June 2011, when then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton hinted at regional connectivity through rail lines, highways, and energy infrastructure — presenting the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline project as an example — in a speech during her visit to India. The initiative aimed at creating a sustainable Afghanistan through regional trade, transit, and infrastructure projects after the withdrawal of international troops in 2014. The announcement was an indication of long term U.S. engagement in the region while holding the interests of its rivals Iran, Russia, and China in check. In this context, the Lapis Lazuli Corridor agreement signed on November 15, 2017 in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan is a strategic move in line with the U.S. strategy for Afghanistan and the region.

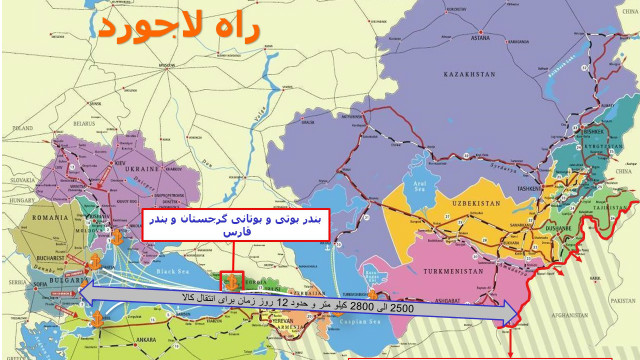

The corridor is a trade and transport route which begins in Aqina and Turghundi ports in the Afghan provinces of Faryab and Herat, reaches Turkmenbashsi port in Turkmenistan, crosses the Caspian Sea and heads to Baku in Azerbaijan and the Georgian capital Tbilisi, reaches Poti and Batomi ports on the Black Sea, and finally crosses via Turkey to Europe. The route involves road, rail, and maritime transport. It took the member countries around three years to discuss and finalize the agreement.

An analysis of the geopolitical position of each member country reveals important implications for the global and regional political economy. The first country, Afghanistan, celebrated the agreement as an important development that would heal its long standing economic plague to a great extent. As a landlocked country, Afghanistan has mainly relied on Pakistan for its international trade in the light of international conventions and bilateral agreements like the Afghanistan Transit Trade Agreement (ATTA) and Afghanistan Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement (APTTA). However, these legal frameworks have not helped; the country’s economy continues to suffer due to transit trade challenges posed by Pakistan. Afghanistan’s disadvantaged geographic position has been used as a pressure tool by Pakistan to dictate its political policies. In this context, the Lapis Lazuli corridor would diversify Afghanistan’s transit routes and has been interpreted as the shortest, cheapest, and most reliable route for Afghanistan’s trade with Europe. Beyond transit trade, the agreement is a strategic step toward the integration of Afghanistan in the region and securing its economic future by designating it as a hub to connect the markets of South Asia, Central Asia, and Middle East.

The next destination of the Lapis Lazuli route is Turkmenistan. The country is the fourth largest producer of natural gas in the world with exports to Russia, China, and Iran. However, revenue from the hydrocarbon industry is shrinking following major back-to-back blows. The Russian giant Gazprom ceased purchasing Turkmen gas, apparently due to a price dispute, in early 2016 while the supply to Iran was stopped due to payment issues at the start of 2017. This has left China as the only major destination for Turkmen gas. However, that trade relationship too has its issues. Turkmen gas is supplied to China through three lines — Lines A, B, and C — passing through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan before reaching western China. In order to boast the supply, an additional 30 billion cubic meter of gas was planned to be supplied through a fourth pipeline, Line D, which was supposed to pass through Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Kyrgyzstan to reach China. However, construction work has remained suspended since December 2015 due to disagreements over the route, and other technical issues among the three transit countries. On the other hand, the implementation of the TAPI gas pipeline project will not be an easy task given the security situation of Afghanistan.

Turkmenistan is aware of the risks associated with its heavy reliance on the hydrocarbon industry and has been planning to diversify the economy. As part of its economic diversification agenda under the strategic national priorities as outlined in the National Program for Socioeconomic Development 2011-2030, it has embarked on an ambitious objective to become a transnational transit corridor, including Black Sea and Caspian Sea connections. As such, Turkmenistan has heavily invested in transport infrastructure. In this context, the Lapis Lazuli Corridor agreement is in line with country’s strategic priorities. It will integrate the country more strongly with the South Caucasus and provide access to a world of economic opportunities.

Across the Caspian Sea, the Lapis Lazuli trade and transport route reaches the U.S. “string of pearls” in the region — Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey. Azerbaijan is a strategic player in the South Caucasus. The country gained independence after the collapse of the Soviet Union and since then, it has tried to maintain a distance from Russia, given its high-handed approach in dealing with smaller neighbors. On the other hand, as a Shiite Muslim majority, the country shares ethnic and religious heritage with Iran. However, despite this, Azerbaijan has maintained its Soviet-era secular status, keeping a distance from Iran in terms of political and economic relations. The close military, economic, and political ties between Israel and Azerbaijan are perceived as anti-Iran by Tehran. As such, both countries have continued to arrest each other’s citizens under conviction of espionage.

In August 2016, Azerbaijan participated in a trilateral summit to discuss regional issues, including the North- South Transport Corridor, with Iran and Russia. The land- and sea-based route aims to link India with Europe via Iran, the South Caucasus, and Russia. The presence of Azerbaijan was surprising given the geopolitical stance of the country. This was largely interpreted as an attention-seeking signal to the United States, as the Obama administration had taken the country for granted. However, Azerbaijan’s decision to sign the Lapis Lazuli agreement is not only aligned with its typical geopolitical stance but would also counter similar regional moves by U.S. rivals Iran, China, and Russia to a great extent.

The next stop of Lapis lazuli Corridor is Georgia, a country which shares borders with Russia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, with Black Sea to its west. For more than two centuries, the country had to seek Western support to fight the influence of its giant neighbors, Russia and Persia. It gained short-lived independence after World War I, before the Bolshevik regime took over the country. The collapse of the Soviet Union granted independence to the country in 1991, but Russia continues to view Georgia as its backyard, like its other small neighbors. The most recent display of power against Georgia appeared when Russia invaded the country in August 2008 and recognized the Georgian territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia as independent states. The action was further interpreted as an attempt to prevent Georgia from getting close to the West by joining NATO.

Georgia is a transit route for Azerbaijani oil and gas to reach Turkey. Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey are focusing on the connectivity among themselves, like South Caucasus Pipeline (a gas pipeline), the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline and Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) railway. These developments are a clear indication of the increased influence and dominant position of Turkey vis-à-vis Russia in the South Caucasus region. The country has already termed the BTK railways as the Turkish version of the New Silk Road Corridor with an ambition, that it would be utilized by North Africans and Europeans to connect with landlocked Central Asia.

Turkey is further aiming to turn into an energy hub for the EU. At the moment, Russia is the biggest supplier of oil and gas to the EU. As part of diversification efforts and to decrease dependence on Russia, the United States and EU are backing initiatives like the Nabucco gas pipeline project, which would carry gas from the Caspian and Middle East to Austria in Central Europe, and turn Turkey into an energy crossroads. The Caspian spur of the Nabucco pipeline can challenge the Russian monopoly and Iranian efforts to supply gas to Europe through the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline, a project suggested by the United States with a construction agreement signed in 1999. On the other hand, it would diversify Turkmen exports and decrease its reliance of China. The pipeline is meant to supply gas not only from Turkmenistan but also Kazakhstan to EU through an underwater pipeline. At the moment, the dispute over territorial boundaries in the Caspian and fierce opposition of Iran and Russia is holding back the project. It is important to mention that mentioned pipeline would reach Turkey via the Lapis Lazuli Corridor countries, i.e. Azerbaijan and Georgia.

In the light of countrywide geopolitical situation presented above, the Lapis Lazuli Corridor coincides with the national priorities of the member countries on one hand and U.S. strategic engagement on the other hand. The corridor has potential to strengthen the political and economic relations of the member countries and as such can pave the way for other initiatives like the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline in the long term. Finally, it can ensure regional development through increased integration and economic cooperation, with implications for overall development in the region.

Shoaib Ahmad Rahim is a development practitioner, lecturer in international economics and analyst on national and regional political economy. Rahim holds an MSc. Degree in Development Economics from University of Sussex, England. Follow him on Twitter: @ShoaibBinRahim

Afghanistan Times

Afghanistan Times